Theism Rewritten for an

Age of Science

Chapter 6 of God

and Science

by Charles P. Henderson, Jr.

The

theologian dies. His wife returns home and walks upstairs to his desk. Hannah

Tillich describes what she discovered: The

theologian dies. His wife returns home and walks upstairs to his desk. Hannah

Tillich describes what she discovered:

| I unlocked the drawers. All the girls' photos fell out, letters and poems,

passionate appeal and disgust. Beside the drawers, which were supposed to contain

his spiritual harvest, the books he had written and the unpublished manuscripts

all lay in unprotected confusion. I was tempted to place between the sacred pages

of his highly esteemed lifework those obscene signs of the real life that he had

transformed into the gold of abstraction--King Midas of the spirit.(1)

| Hannah Tillich's autobiography contains a brief, brutally

honest account of the theologian's personal life. It portrays the Paulus she knew

as husband and lover; it shows in concrete detail the situation of passion in

which many of Tillich's ideas were conceived and nurtured. Like no other record

in western literature, From Time to Time reveals what it was like to

be life's companion to a titan of the spirit. Reading this book, many would

discount Tillich as a theologian. After all, why is a teacher in the church of

God defiant of so many of the rules in conventional morality? Why the extra-marital

relationships, the menage-a-trois, the experimentation with drugs, the Marxism,

and, most remarkable of all, the development of a theological system that rests

upon the premise that God does not exist! When Hannah's book is read alongside

all the other Tillich books and, when the patterns of his whole life and work

emerge from the immediate passions of their marriage, the answers to these questions

become obvious. Hannah opened the desk containing Tillich's treasury of love letters

nestled alongside his theological writings, and she has this fantasy. With a depth

of conflicting emotion she imagines placing "between the sacred pages of

his highly esteemed lifework those obscene signs of the real life that he had

transformed into the gold of abstraction." These words are descriptive.

It would not be far off the mark to say that Tillich did turn the deepest passions

of life into the gold of abstraction. That is exactly what a theologian is supposed

to do. The fire of religious feeling -- faith and doubt, wonder, and awe -- must

be translated into an orderly pattern so that one may see and understand the fire's

source. If one wants to learn from the religious experience of another person,

one must have the instruments of thought necessary to discern what may be of value

in a particular experience and what may not be of value. Historically,

the church has lost its way when its abstractions were no longer in touch with

"real life" and no longer served a human need. Whenever the words of

piety, sermons, or prayers are invoked in mindless repetition and whenever the

words of the theologians no longer bear any relationship to the actual passions

of a particular people, then it is time to mourn for the church of Christ. One

of Tillich's greatest contributions to theology, far greater than his mastery

of abstraction, was his demonstration of exactly how deeply religious passion

is rooted in human life itself. Tillich would have considered it a compliment

to say that he succeeded in making the deepest thoughts and feelings accessible

to understanding. Of course, Hannah's comment was not meant to be complimentary.

She was referring to the tragedy of Midas, suggesting exactly what many of Tillich's

theological opponents have charged: that he transformed life itself into an abstraction;

that he turned the reality of God into the deadly gold of fanciful theory.  Thus,

in the bitterness of her mourning Hannah imagines placing the love letters in

between the pages of his theology, and, ironically, that act would have been appropriate.

For, as Tillich struggled with the many loves and lovers in his life, he also

struggled with the deepest and most imponderable love of all, the love of God.

Tillich's most formidable work, the weighty, three volumes of his Systematic

Theology could be described as a thoughtful record of one man's exploration

into the depths of love. What Hannah says of the love letters can also be said

of the theology. In the papers contained within Tillich's secret desk she could

see "the many-colored flow of emotions he had aroused and that had aroused

him -- the red of passion, the sharp poisonous yellow of competition, the black

of despair, the blue of devotion, and even the white of innocence he had not been

able to destroy."(2) There were these and

many other shades and hues of emotion represented in the letters and in the theology.

For in his writings Tillich was able to discern the inner symmetry of the human

spirit; he was able to explore the geography of human consciousness itself. In

so doing he drew upon the newest of the life sciences, depth psychology. Almost

single-handedly Tillich was able to separate the science of psychoanalysis from

the atheism of its founder, Sigmund Freud, and to use its powerful tools of analysis

in rebuilding the very faith which Freud so confidently assigned to oblivion.

Though one may not find in Tillich a life one wants to emulate, one most certainly

finds in his theology a number of insights indispensable to the renewal of religion

in an age of science. Thus,

in the bitterness of her mourning Hannah imagines placing the love letters in

between the pages of his theology, and, ironically, that act would have been appropriate.

For, as Tillich struggled with the many loves and lovers in his life, he also

struggled with the deepest and most imponderable love of all, the love of God.

Tillich's most formidable work, the weighty, three volumes of his Systematic

Theology could be described as a thoughtful record of one man's exploration

into the depths of love. What Hannah says of the love letters can also be said

of the theology. In the papers contained within Tillich's secret desk she could

see "the many-colored flow of emotions he had aroused and that had aroused

him -- the red of passion, the sharp poisonous yellow of competition, the black

of despair, the blue of devotion, and even the white of innocence he had not been

able to destroy."(2) There were these and

many other shades and hues of emotion represented in the letters and in the theology.

For in his writings Tillich was able to discern the inner symmetry of the human

spirit; he was able to explore the geography of human consciousness itself. In

so doing he drew upon the newest of the life sciences, depth psychology. Almost

single-handedly Tillich was able to separate the science of psychoanalysis from

the atheism of its founder, Sigmund Freud, and to use its powerful tools of analysis

in rebuilding the very faith which Freud so confidently assigned to oblivion.

Though one may not find in Tillich a life one wants to emulate, one most certainly

finds in his theology a number of insights indispensable to the renewal of religion

in an age of science.

Paul Tillich was born on August 20,1886, in a Lutheran

parish house in Starzeddel, Germany. He was the firstborn son of Johannes and

Mathilde Tillich. Writing to his parents about the infant, Johannes Tillich said,

"Little Paul is still alive but his life is a continuous struggle with death."(3)

The immediate threat to his life soon passed, but the theme struck in this early

report was echoed again and again in the maturity of the theologian. Johannes

Tillich was a Lutheran pastor who eventually rose to a position

of some power in the hierarchy of the Evangelical Church of Prussia. He was very

much an authority figure for his son, yet there was a depth of love between them

which was often felt if seldom expressed. Tillich also had a close relationship

with his mother, Mathilde. She was strict and insistent, but the bonds of affection

between mother and son grew stronger and stronger even as she fell victim to cancer

in her early forties. Shortly before his mother's death he said to her, "I

would like to marry you?" Later Tillich summarized her influence: "My

whole life was embedded in her. I couldn't imagine any other woman."(4)

Growing up in the parsonage, Tillich attended grammar

school directly across the street from the church where his father was pastor.

At home Tillich learned the meaning of the Christian holidays and seasons; in

school he was instructed in the catechism, learned the great hymns of the church,

and studied the Bible. In church he was exposed to the sacraments and other rituals

of the Christian faith. As his biographers, Wilhelm and Marion Pauck, put it:

| In the

center of the town stood the church; in the center of the year was the festival

of Christmas; all else revolved around this place and this event. His feelings

for the ecclesiastical and sacramental were for him part of the fabric of life

from the very beginning.(5) | Yet

Tillich's religious experiences were not limited to these traditional forms. When

he was only eight, upon seeing the Baltic Sea for the first time, he felt the

presence of the "infinite." This early experience was repeated and extended

in both scope and depth throughout his life. As he writes in his short autobiography:

| The weeks

and, later, months that I spent by the sea every year from the time I was eight

were even more important for my life and work. The experience of the infinite

bordering on the finite ... supplied my imagination with a symbol that gave substance

to my emotions and creativity to my thought.... Many of my ideas were conceived

in the open and much of my writing done among trees or by the sea.(6)

| Tillich reports that "all the great

memories" of his life were interwoven with scenes from nature, with images

of the landscape, with sea and soil, with the smell of the potato plant in autumn

and the pine tree in spring. Yet at the same time Tillich was also fascinated

by the city. "Visits to Berlin,

where the railroad itself struck me as something half-mythical... developed in

me an often over-powering longing for the big city."(7)

It was in the city, first the cities of Germany, especially Frankfurt and Berlin,

and later in America, especially New York, that Tillich was exposed to the cultural

and social diversity that were as important to him as the solitudes and silences

of nature. Throughout his life Tillich loved to travel from city to city and from

countryside to countryside. He would travel alone or he would travel with Hannah.

In fact it was their traveling which Hannah remembers as the cement of their often

troubled marriage.

Perhaps our moment came in our travels together. I was not

only the listener for his geographical, historical, and philosophical-theological

knowledge. I had studied art, I could show him lines, composition, color, technique,

and the intuition of my own enthusiasm.... I could sense the flavor of past centuries,

I could make the poems of the great and the faces of the kings come alive for

him.(8)

| As

he was to cross so many borders and oceans during his life, so Tillich adopted

"the boundary line" as an image which depicted and defined his stance

in the world of thought. Throughout his career he found himself walking the narrow

line between the temperament of his mother and his father, between the beauty

of the countryside and the fascination of the city, between the church and secular

culture, between politics and philosophy, between science and theology. In fact,

his entire theological system begins with what Tillich called the "method

of correlation." Tillich saw with stunning clarity the futility of a faith

which provides answers to questions no one is asking; he saw the absolute necessity

of making connections between the several dimensions of experience. While serving

as an assistant minister in the Moabit, or workers' neighborhood of Berlin, Tillich

found himself teaching a confirmation class. Trying to communicate the Christian

faith to his students, he found the word "faith" itself to have little

meaning and the meanings that still remained in such traditional vocabulary to

be totally inadequate.

| This discovery determined his way of being a theologian:

early in his process of development he cast his lot with the apologetic theologians,

namely those who attempt to interpret the Christian faith by means of reasonable

explanation. Tillich understood this to mean that one must learn "to defend

oneself before an opponent with a common criterion in view.(9)

|  In

his introduction to Systematic Theology Tillich notes that the apologetic

theologian searches for the "common ground" beneath the feet of those

who articulate the faith and those to whom faith would speak. He acknowledges

the possibility that in seeking a common understanding with those outside the

theological circle, the theologian runs the risk of compromising faith. Yet the

alternative approach suggested by "kerygmatic" theologians like Karl

Barth is still less appealing. In Tillich's view one can no longer proclaim the

faith, as it were, from a mountaintop. The Christian message cannot be "thrown

like a stone"(10) at its target. Such an

approach might seem acceptable to a theologian who can take refuge in the faith

as though it were an impregnable fortress, but for Tillich no such refuge existed.

Even within the relative serenity of the parsonage during his adolescence, he

found that doubt about some of his father's deeply held beliefs could not be silenced.

Fortunately, Tillich found a friend and confidant in Eric Harder, his father's

assistant. The young minister not only listened to his questions but also accepted

his doubts. Through the relationship with Harder Tillich realized that Christianity

might not be wholly contained within his father's narrow orthodoxy. Also, during

his years at secondary school Tillich began reading widely in philosophy, and

as graduation approached he decided to pursue his questions about God one step

further. In 1905 he registered at the University of Berlin, majoring in theology.

Though he seriously considered following his father into the ministry, he also

was drawn toward philosophy, a vocation which eventually led to his appointment

as Professor of Philosophical Theology at New York's Union Theological Seminary

in 1937. In

his introduction to Systematic Theology Tillich notes that the apologetic

theologian searches for the "common ground" beneath the feet of those

who articulate the faith and those to whom faith would speak. He acknowledges

the possibility that in seeking a common understanding with those outside the

theological circle, the theologian runs the risk of compromising faith. Yet the

alternative approach suggested by "kerygmatic" theologians like Karl

Barth is still less appealing. In Tillich's view one can no longer proclaim the

faith, as it were, from a mountaintop. The Christian message cannot be "thrown

like a stone"(10) at its target. Such an

approach might seem acceptable to a theologian who can take refuge in the faith

as though it were an impregnable fortress, but for Tillich no such refuge existed.

Even within the relative serenity of the parsonage during his adolescence, he

found that doubt about some of his father's deeply held beliefs could not be silenced.

Fortunately, Tillich found a friend and confidant in Eric Harder, his father's

assistant. The young minister not only listened to his questions but also accepted

his doubts. Through the relationship with Harder Tillich realized that Christianity

might not be wholly contained within his father's narrow orthodoxy. Also, during

his years at secondary school Tillich began reading widely in philosophy, and

as graduation approached he decided to pursue his questions about God one step

further. In 1905 he registered at the University of Berlin, majoring in theology.

Though he seriously considered following his father into the ministry, he also

was drawn toward philosophy, a vocation which eventually led to his appointment

as Professor of Philosophical Theology at New York's Union Theological Seminary

in 1937.

Tillich's

progress within the academic profession was interrupted, however, and his life

turned completely around by World War I. Suddenly Tillich found himself headed

toward the front, filled with nationalistic fervor and even enthusiasm over the

opportunity to serve both God and country as a military chaplain. The realities

of war changed all that. As Tillich put it years later, he and his compatriots

in the military "shared the popular belief in a nice God who would make everything

turn out for the best:(11) It became increasingly

impossible to affirm the benevolence of God in the face of the horrors of trench

warfare. Tillich's

progress within the academic profession was interrupted, however, and his life

turned completely around by World War I. Suddenly Tillich found himself headed

toward the front, filled with nationalistic fervor and even enthusiasm over the

opportunity to serve both God and country as a military chaplain. The realities

of war changed all that. As Tillich put it years later, he and his compatriots

in the military "shared the popular belief in a nice God who would make everything

turn out for the best:(11) It became increasingly

impossible to affirm the benevolence of God in the face of the horrors of trench

warfare.

One of the duties of the chaplain was to bury the dead. As the

violence of the war intensified, Tillich found himself spending more time digging

graves than attending to his sacramental duties. In November 1916 he wrote to

a friend noting his mounting sense of despair in the face of so much dying:

| I have constantly the most immediate and very strong feeling

that I am no longer alive. Therefore I don't take life seriously. To find someone,

to become joyful, to recognize God, all these things are things

of life. But life itself is not dependable ground. It isn't only that I might

die any day, but rather that everyone dies, really dies, you too,--and

then the suffering of mankind... not that I have childish fantasies of the death

of the world, but rather that I am experiencing the actual death of this our time.(12)

| More and more Tillich came to the realization

that a certain God had died on the battlefields of Europe. The nice God who would

make all things work out for the best had died. Tillich realized that the war

had given concrete shape to the doubts of his adolescence. It was not only his

doubts or his skepticism that prevented him from giving unqualified

assent to God; but it was also the situation of total war which brought God universally

into question. One could no longer easily preach about the benevolence of God

or issue promises of peace from the heights of the mountaintop when the whole

of western civilization seemed to be dying.  Did

the war reveal the fatal flaws of capitalism? Was nationalism nothing less than

the politics of death? Theological questions about the death of God were matched

and mirrored by political questions about the self-destructiveness of nations

and empires. Tillich began to see that his experience of God's absence was related

to the experiences others were having, if in different form and context. Existentialist

philosophy, Freudian psychology, and Marxist social theory explored the tragic

depths of life and revealed the full force and power of the demonic. Doubt, death,

and the demonic, three dark themes for Tillich, came to the forefront of his awareness

during the war. Still Tillich gained more from the war than the courage

to trust his doubt. As a diversion from the terror of the battlefield, he and

his friends would entertain themselves by studying picture-postcard reproductions

of the world's great art works. For the first time Tillich began to see the

importance of art. He found that he could escape the dread of the battlefield

by contemplating the beauty of an expressionist painting, for example. The Expressionists

did not merely reproduce the suface detail of objects of the world; houses,

trees, and human beings were not for them what appears through the lens of a camera.

Looking at an expressionist landscape one can see the inner light of things. One

sees in their painting a dimension of depth lacking in realist paintings.

Does the light one sees in such a painting have any relationship to the light

that comes from God? Tillich found, as he kept looking at the paintings, that

he was doing theology; he saw that in the dimension of their greatest depth all

art and, in fact, all life evokes a religious response. Tillich reacted to the

war and the politics of death by committing himself to be a theologian of life.

|

Wassily Kandinsky -- Composition V 1911

Theme: The Resurrection of the Dead | However,

for a second time his course was altered radically and forever by an upheaval

in his personal life. During the war his wife, Grethi Wever, had fallen in love

with one of his closest friends. Having lost their first child in infancy, Grethi

now announced that her affair with Richard Wegener had resulted in pregnancy.

In June 1919 Grethi gave birth to her second child, whom Tillich named Wolf. Although

Grethi soon left Tillich, she never married Wegener, and ironically the friendship

between the two men survived both the betrayal and the subsequent divorce. More

importantly, Tillich's reaction to the loss of his marriage was to plunge into

what was to become a lifelong search for a new style of living, unfettered by

what he increasingly saw as the chains of conventional morality. Tillich transformed

his Berlin apartment into a "pension" for artists, writers, students,

and others who were exploring the new possibilities of the "bohemian."

Increasingly Tillich was drawn to the theater, to poetry and dance, to literature

and every form of art. He would spend his free hours writing in a cafe and would

gather around him friends, both male and female, who shared his interests in politics,

psychoanalysis, philosophy, and the arts. The threads of these several interests

were spun into the fabric of his lectures delivered at the University of Berlin,

as well as his sermons and scholarly articles. In January 1920 Tillich

suffered the death of his sister Johanna. Ever since the passing of his mother,

Paul and Johanna had relied upon each other for the primal support and nurturing

which can come only when siblings struggle through the stages of rivalry toward

genuine intimacy. In February, as he still suffered with the depression which

had followed Johanna's death, Tillich met Hannah Werner, an art teacher and poet,

at a Mardi Gras costume party. In the weeks that followed they were plunged into

a passionate, stormy affair which continued to deepen even though Hannah insisted

upon carrying forward her plans to marry another man, Albert Gottschow. For two

long years Hannah lived through the initial stages of a marriage that seemed doomed

from the onset. Finally, after giving birth to a son (who soon died), she moved

back to Berlin to join Tillich. Hannah and Paul were married in March 1924, but

the ambivalence of their relationship continued and the struggle between them

intensified. Fifty years before the idea of the "open marriage" provided

the pretext for a best selling book of the same tide, the Tillichs entered upon

their marriage determined to defend their freedom in the face of all conventional

notions of fidelity. In Tillich's view, keeping faith with another person had

little to do with the exclusion of other relationships; the essence of fidelity

was the ongoing commitment to a relationship of depth and passion. As long as

one remained faithful to the depth of a relationship, what reason remained for

the sacrifice of freedom? Thus in the 1920s the Tillichs worked out for themselves

what they referred to as their "erotic solution."(13)

Together they constructed a life in defiance of conventional morality. Together

they set out to discover what the depths of love would reveal if their marriage

were lived out without restraint against freedom. Though Hannah's book may not

be a completely accurate record of their experience through forty years of marriage,

still it is clear that in their marriage they shared both the depths of pain and

the heights of ecstasy. Through the length and breadth of their relationship they

did not cease to struggle with both the demonic and the divine, both the depths

and the abyss of love (to use Tillich's abstractions in their exact context).

It is crucial to remember that this "experimental" marriage did

not arise out of hedonism or self-indulgence. In a sense the marriage was consummated

out of the tragedy of war and in the darkness of the shadow of death. As the nice

and innocuous God of popular religion had died with so many millions of young

men upon the battlefields of Europe, so the veil of respectability had been torn

from the face of bourgeois morality. If the good Christian folk of Europe, Protestant

and Catholic, could allow the entire continent to be ravaged by war, what value

could be found in a popular morality which condemned the slightest aberrations

in personal behavior, even as it tolerated and even justified the politics of

total war? When Tillich looked back upon the conditions leading to the

war, he included in his diagnosis the exact problem I have been discussing in

this book; namely, the tragic cleavage that divides the scientific from the theological.

Tillich used one of the new psychological terms, calling it the "schizophrenic

split in our collective consciousness." As he saw so clearly, the bewilderment

and confusion of this age is rooted in the separation of science from religion,

a condition which drives "the contemporary mind into irrational and compulsive

affirmations or negations of religion."(14)

In the period since Tillich's death it has become more and more apparent

that the contemporary mind is also driven into compulsive affirmations or negations

of science. As people see religion as a source of salvation and dangerous fanaticism,

science is also seen as a source of lifesaving discoveries and the most terrible

instruments of death. For Tillich, this situation required nothing less than a

new understanding of God, a new theology which would take seriously the science

of the last two hundred years. Perhaps the primary reason that scientists

and theologians have not engaged in more serious, productive conversation has

been their shared misconception of God. From within the circle of faith and from

without, religion is defined as an attempt to enter into relationship with a divine

being. Hence the dialogue between science and religion is quickly aborted when

theologians seem to be asserting the existence of something that science seems

to deny; namely, an all-powerful, personal God. It is precisely this impasse that

Tillich addresses throughout the length and breadth of his theology.

It is just this idea of religion which makes any understanding

of religion impossible. If you start with the question whether God does or does

not exist, you can never reach Him; and if you assert that He does exist, you

can reach Him even less than if you assert that he does not exist. A God whose

existence or nonexistence you can argue is a thing beside others within the universe

of existing things.... It is regrettable that scientists believe that they have

refuted religion when they rightly have shown that there is no evidence whatsoever

for the assumption that such a being exists. Actually, they have not only not

refuted religion, but they have done it a considerable service. They have forced

it to reconsider and to restate the meaning of the tremendous word God. Unfortunately,

many theologians make the same mistake. They begin their message with the assertion

that there is a highest being called God, whose authoritative revelations they

have received. They are more dangerous for religion than the so-called atheistic

scientists. They take the first step on the road which inescapably leads to what

is called atheism. Theologians who make of God a highest being who has given some

people information about Himself, provoke inescapably the resistance of those

who are told they must subject themselves to the authority of this information.(15)

| So Tillich began what was the

fundamental purpose of his theological endeavor: "to reconsider and to restate

the meaning of the tremendous word God. In so doing he used his "method

of correlation" to make the connections between questions that arise out

of the life situation of a particular people and the vast resources of the Christian

tradition. If there were to be real communication between scientist and theologian,

then Tillich must be able to identify a "common ground" between those

two disciplines. Given his background and training in philosophy, it is perhaps

not surprising that he concluded:

| The point of contact between scientific research and theology

lies in the philosophical element of both. ... Therefore, the question of the

relation of theology to the special sciences merges into the question of the relation

between theology and philosophy.(16) |

Tillich argued that in every scientific theory there

was an element of philosophy, as in every theology, there is an implied philosophy.

For American readers the meaning of these assertions will be difficult

to grasp. Tillich is speaking out of a philosophical tradition that has never

taken root in America. For Tillich, philosophy appeared to be a bridge between

science and religion, but, where Tillich saw a carefully constructed bridge, many

readers of this book may find a gaping chasm. This may reflect one’s lack

of familiarity with German philosophy, but it must also be noted that the philosophical

traditions in which Tillich stood have been subject to the same criticism as religion

itself. For Tillich, philosophy was the study of those

| structures, categories and concepts which are presupposed

in the cognitive encounter with every realm of reality. From this point of view

philosophy is by definition critical. It separates the mulifarious materials of

experience from those structures which make experience possible.(17)

| Whereas science, in its ever-increasing powers

of research, constantly expands the "multifarious materials" of human

experience, philosophy attempts to illuminate the skeletal elements of consciousness

itself. For Tillich, philosophy could function as the connecting link between

science and theology because abstract thought had for him a direct relationship

to experience; Tillich's abstractions were ontological and existential, but it

is precisely the relationship to experience which has become so problematic today.

Therefore many readers of Tillich would conclude that Hannah was correct in her

criticism. As a philosopher Tillich does appear to be a King Midas of the spirit,

and the gold of his abstractions is a poor substitute for either the warmth of

emotion or the burning clarity of the senses. Drawing upon his background in philosophy

Tillich spoke of God as the Ground of Being or alternatively as Being Itself.

He spoke also of the Absolute and the Unconditioned, but today these terms are

as problematic as a God who is conceptualized as a being existing alongside of

all other beings.

Fortunately,

however, Tillich had another way of defining the relationship of science and religion

and therefore another solution to the "schizophrenic split in our collective

consciousness." Tillich began his career in Germany but he ended it in the

United States. Having been dismissed by the Nazis from his teaching post at the

University of Frankfurt in 1933, he migrated to New York where he joined the faculty

of Union Theological Seminary, continuing at that school for twenty-two years.

Interpreting his ideas to an American audience, Tillich utilized the tools of

analysis made available by depth psychology. Fortunately,

however, Tillich had another way of defining the relationship of science and religion

and therefore another solution to the "schizophrenic split in our collective

consciousness." Tillich began his career in Germany but he ended it in the

United States. Having been dismissed by the Nazis from his teaching post at the

University of Frankfurt in 1933, he migrated to New York where he joined the faculty

of Union Theological Seminary, continuing at that school for twenty-two years.

Interpreting his ideas to an American audience, Tillich utilized the tools of

analysis made available by depth psychology. In his theories of the unconscious

Sigmund Freud had brought to light a dimension of depth in human consciousness

which the narrow rationalism of the nineteenth century had not allowed. In scientific

terms Freud had achieved what Tillich described as "the emancipation of psychology

from domination by physiology." Freud's great achievement was to defeat the

notion that consciousness could be reduced to its physical underpinnings and then

explained as a biological or chemical process.

This discovery was important ethically and religiously particularly

because it recognized--with questionable over-emphasis, to be sure--the fundamental

importance of the erotic sphere for all aspects of the psychical life. It was

an insight of which religion has ever been aware and which only the conventions

of bourgeois society have relegated to the limbo of forgotten truth.... Speaking

in the language of religion, psycho-analysis and the literature allied with it

cast light upon the demonic background of life. But wherever the demonic appears

there the question as to its correlate, the divine, will also be raised.(18)

| While Freud insisted that his

theories had discredited the truth claims of religion, Tillich saw that psychoanalysis

actually confirmed many elements of religious tradition. Freud insisted that belief

in God represented nothing more than the projection of images from the erotic

experience of the infant into a supernatural realm, but Tillich drew the obvious

parallels between that process and the biblical notion of idol worship and idolatry.

He also turned Freud upside down when he suggested that, even when one sees that

every idea and image of God is a projection, one must then follow the metaphor

one step farther and notice that

| projection always is projection on something--a

wall, a screen, another being, another realm.... The realm against which the divine

images are projected is not itself a projection. It is the experienced ultimacy

of being and meaning. It is the realm of ultimate concern. (19)

| When Tillich writes metaphorically of the

screen "against which the divine images are projected" he is certainly

not referring to an object which exists like the screen in a movie theater. Tillich

is not referring to something "out there." "It is the experienced

ultimacy." One can always trace Tillich's most obscure abstractions back

to the immediacy of human experience. That is why Tillich found such fertile soil

in psychoanalytic theory. Freud had illuminated the pathways into the depths of

human experience, and Tillich followed Freud's lead relentlessly; increasingly

he spoke of religion as "the dimension of depth." In

a short but highly suggestive study of Biblical Religion and the Search for

Ultimate Reality, first written as a series of lectures at the University

of Virginia in 1952-53 and later published as a book, Tillich pulled together

the philosophical and psychological elements in his thought to demonstrate that

the truth claims of the Bible are in fact compatible with the deepest insights

of science.

| If we enter the levels of personal existence which have been

rediscovered by depth psychology, we encounter the past, the ancestors, the collective

unconscious, the living substance in which all living beings participate. In our

search for the "really real" we are driven from one level to another

to a point where we cannot speak of level any more, where we must ask for that

which is the ground of all levels, giving them their structure and their power

of being.(20) | It

is supremely ironic that while Freud thought he was driving God out of the sky,

his theories in fact illuminate the very soil in which human experience of the

holy is most deeply rooted and grounded. In Tillich's supple hands the tools of

analysis supplied by Freud had been put in service to theology, and the same is

true of the tools which Karl Marx provided. In fact, Freud and Marx performed

much the same function within Tillich's theological system.

| Marxism can be understood as a method for unmasking hidden

levels of reality. As such, it can be compared to psychoanalysis. Unmasking is

painful and, in certain circumstances, destructive. Ancient Greek tragedy, e.g.

the Oedipus myth, shows this clearly. Man defends himself against the revelation

of his actual nature for as long as possible. Like Oedipus, he collapses when

he sees himself without the ideologies that sweeten his life and prop up his self-consciousness.

The passionate rejection of Marxism and psychoanalysis, which I have frequently

encountered, is an attempt made by individuals to escape an unmasking that can

conceivably destroy them. But without this painful process the ultimate meaning

of the Christian gospel cannot he perceived.(21)

|

When Tillich writes of the violent and passionate reactions against

Marxism, he is not merely speaking of a violence of emotion. During his final

days in Germany, as Adolf Hitler began to exercise the dictatorial powers voted

him by the Reichstag in March of 1933, Tillich saw his own study of Marxism,

The Socialist Decision, first banned and then burned during a Nazi demonstration

in the streets of Frankfurt. Hitler had manipulated the fear of communism and

revolution from the left as a justification for his own revolution from the right.

In burning Tillich's book, however, the Nazis were only demonstrating their utter

disregard for the truth which could have saved them from the most terrible form

of fanaticism, the fanaticism that comes from within. Tillich's book was

radical in the true sense of that word; it pursued the dialectics of Marxism and

the doctrines of Christianity to their roots. It raised the basic question as

to why Marx had turned against religion at the same time as it addressed the similarly

hostile reactions of religious people against Marxism. As he pursued these questions

Tillich arrived at the somewhat surprising conclusion that this mutual hostility

can be explained largely by the misunderstandings of science on both sides of

the conflict. "The attitude of socialism toward religion could never have

been as negative as it has become, if socialism had not thought that it had a

substitute for religion as its disposal, namely, science.(22)

Likewise, as Tillich demonstrates, the attitude of religious people toward

socialism could never have been as hostile if the church had not accepted Marx's

false premise that science is the deadly enemy of faith. Thus, behind and beneath

the conflict between communism and Christianity stands the larger conflict over

science, and the tragedy which Tillich saw unfolding in Nazi Germany could be

repeated in different shapes and sizes until and unless the original misunderstandings

are unraveled.

|

Nazis burn Tillich's

The Socialist

Decision

and other books. | In

the years prior to World War II Tillich laid the theoretical foundations for what

he called "belief-ful realism." He hoped that a dialogue between socialists

and Christians could lead both to a politics filled with prophetic passion but

without fanaticism and to a religion fueled by a hunger for justice but without

the utopian idealism that would prevent it from ever being put into practice.

Tillich looked forward to a new age "where the static opposition of socialism

and religion would give way to a new synthesis characterized by economic justice

and an awareness of the... divine in everything human.(23)

By contrast to this development, Tillich saw both

capitalism and communism moving in a similar direction and making the same mistake.

Both of them, in the name of science, have tended to exclude the element of the

eternal in all things temporal. Describing this tendency in capitalist economies,

Tillich writes:

| In the past man's relation to material things was hallowed

by reverence and awe, by piety toward and gratitude for his possessions. In the

precapitalist era there was something transcendent in man's relation to things.

The thing, property, was a symbol of participation in a God-given world.(24)

| By contrast, in the advanced stages of capitalism

objects and possessions tend to lose their deeper, symbolic meaning. "They

become utility wares, conditioned wholly by their utility... produced, treated

and given away without love or a sense of their individuality."(25)

Despite their differences both capitalism and communism have stripped away the

religious meanings attached to material commodities and in the name of "scientific

objectivity" have promoted an instrumental attitude toward the natural world.

In this process capitalism tends to deteriorate into the merely competitive, the

war of all against all, and communism into naked coercion. In both societies the

mind of the mass prevails over the individual, and personhood is reduced to a

series of numbers on the latest personality profile. As Tillich followed

Freud into the depths of human consciousness, exploring the sources of both the

erotic and the demonic to the point where the question of the divine presented

itself, so he followed Marx into the depths of social structures and societies,

exploring the sources of evil and injustice to the point where the questions of

justice are raised with prophetic passion. In other words, Tillich used the theories

developed by Freud and Marx, exploring the mysteries of personal and social life,

to the point where the theological implications began to be apparent. Following

these atheists onto their own terrain and pursuing their paths of inquiry even

deeper into the human predicament, Tillich was able to advance a new case for

theism or, rather, a new theism framed in terms appropriate to an age of science.

Tillich asserted that a critical, logical, and strictly scientific analysis of

the human situation reveals "the presence of something unconditional within

the self and the world"; or, putting it another way, "an awareness of

the infinite is included in man's awareness of finitude.(26)

Does this line of reasoning constitute a new proof

for the existence of God? Did Tillich discover a new argument for God spun out

of the very theories that lie at the heart of scientific atheism? One can answer

those questions in the affirmative only by using Tillich against Tillich. For

he continually asserted that the existence of God is not open to argumentation.

The existence of God is not something that can be proved or disproved. There are

many direct statements to this effect in Tillich. For example, in the first volume

of his Systematic Theology he writes:

It would he a great victory for Christian apologetics if

the words "God" and "existence" were very definitely separated

except in the paradox of God becoming manifest under the conditions of existence....

God does not exist. He is being-itself beyond essence and existence. Therefore,

to argue that God exists is to deny him.

The method

of arguing through to a conclusion also contradicts the idea of God. Every argument

derives conclusions from something that is given about something that is sought.

In arguments for the existence of God the world is given and God is sought....

But, if we derive God from the world, he cannot be that which transcends the world

infinitely.(27)

| It

is the shortest sentence in this passage which stands out: "God does not

exist"; but those words have a different meaning in context than they have

out of context. Tillich asserts that existence is not an attribute one can use

to qualify God. Tillich is not the atheist attempting to prove that there is no

God, he is the fully committed theist trying to state in the sharpest and clearest

possible way that God is "beyond essence and existence." Traditional

arguments for the existence of God actually diminish God's importance by placing

God alongside of and on a par with all other things, objects, persons, or beings.

God does not exist in this narrow and limited sense. For emphasis alone, therefore,

Tillich puts it in one round sentence. "God does not exist." In the

sentence just preceding this, however, there is a gaping loophole, a giant exception.

"God does not exist" follows hard upon this proviso: "except

in the paradox of God becoming manifest under conditions of existence."(28)

Earlier in the same volume Tillich himself introduces

the possibility that theologians may be able to prove not merely the existence

of God but also the truthfulness of the entire Christian message. In defining

his vocation, Tillich writes:

It is the task of apologetic theology to prove that the

Christian claim also has validity from the point of view of those outside the

theological circle. Apologetic theology must show that trends which are immanent

in all religions and cultures move toward the Christian answer.(29)

| If this were all one could get by way

of a proof for God, it would be all one needs. While rejecting traditional arguments

for the existence of God, Tillich introduces an argument of his own in the concept

of "theonomous culture." As a theologian, Tillich saw it as his primary

responsibility to point out the hidden religious dimensions in every realm of

life. In art and architecture, in politics and economics, in psychology and sociology,

in biology and physics, Tillich found confirmation of the Christian faith. The

Christian doctrine of the incarnation affirms that the divine has become manifest

in human life. Applying this doctrine to the cultures of Europe and America and

drawing upon his knowledge of civilization as a whole, Tillich tried to show that

every cultural creation--a painting, a law, a political movement--has a religious

meaning to be explored and a theological element to be explained. For Tillich

the idea "secular culture" is a contradiction in terms, for even in

a society which is militant in its atheism there is a hidden faith. Thus, as we

have seen, the force of Marxism lies precisely in its success at becoming a substitute

for religion, and the power of psychoanalysis is its rediscovery of the depth

in human personality which is precisely the soil from which religion grows. Tillich

summarized these conclusions in his famous aphorism "Religion is the substance

of culture, culture is the form of religion."(30)

Beyond this distinction between substance and form,

Tillich had a more concrete image to express the relationship of religion to culture

and especially to science. He spoke of science and religion as interpenetrating

dimensions. Tillich saw in this image a solution to the serious problem raised

by the metaphor of levels. For example, one way of distinguishing religion from

science has been to say that religion deals with the soul and science with the

body, religion with the spiritual and science with the material. However, it is

this image which lies at the heart of our present conflict. For, as science explains

more and more of human experience by its own tools of analysis, religion finds

itself retreating onto a higher and higher level until it reaches such a great

height that it no longer has any relevance to the basic processes of life. The

decline of religion in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries has been the result

of this multileveled analysis in which religion gradually recedes onto an ever

more nebulous and remote plane of pure spirituality. By replacing the notion of

hierarchical levels with the image of interpenetrating dimensions, Tillich was

able to distinguish the scientific from the theological while still illuminating

their close relationship. The separate dimensions move out in different directions,

but they all meet around a common axis.(31)  Tillich's

image of "the multidimensional unity of life"(32)

sets the stage for his discussion of the most difficult problem at the interface

of science and theology; namely, the tendency of science to define nature in terms

of mechanical law and the insistence of religion that reality is, in its deepest

dimension, personal. Christianity and all biblical religions are irrevocably committed

to a personal God. Unless one can somehow bridge the gap that has opened up between

the impersonal laws of nature and the personal God of biblical religion, the "schizophrenic

split in our collective consciousness" will not and cannot be healed. Tillich

addressed this problem directly in a paper written in reply to an address by Albert

Einstein. The great physicist had spoken of the relationship of "Science,

Philosophy, and Religion" at a conference on that topic held in September

1940 in New York City. Einstein identified God with the orderly laws of nature

and he emphatically rejected the idea of a personal God. Einstein attacked the

biblical notion of God from four sides. He asserted that the notion of a personal

God is not essential for religion, that it is a mere superstition, that it is

self-contradictory, and, most importantly, that it is incompatible with science. Tillich's

image of "the multidimensional unity of life"(32)

sets the stage for his discussion of the most difficult problem at the interface

of science and theology; namely, the tendency of science to define nature in terms

of mechanical law and the insistence of religion that reality is, in its deepest

dimension, personal. Christianity and all biblical religions are irrevocably committed

to a personal God. Unless one can somehow bridge the gap that has opened up between

the impersonal laws of nature and the personal God of biblical religion, the "schizophrenic

split in our collective consciousness" will not and cannot be healed. Tillich

addressed this problem directly in a paper written in reply to an address by Albert

Einstein. The great physicist had spoken of the relationship of "Science,

Philosophy, and Religion" at a conference on that topic held in September

1940 in New York City. Einstein identified God with the orderly laws of nature

and he emphatically rejected the idea of a personal God. Einstein attacked the

biblical notion of God from four sides. He asserted that the notion of a personal

God is not essential for religion, that it is a mere superstition, that it is

self-contradictory, and, most importantly, that it is incompatible with science.

Tillich's response to these arguments was published as chapter IX in his

Theology of Culture. He answers Einstein point by point. Typically Tillich

starts with a point of agreement. He immediately seeks the common ground on which

a physicist and a theologian may begin. Certainly, he concedes, the concept of

a supernatural being who intervenes in history and interferes with natural events

is incompatible with science. If the universe were run by a deity who arbitrarily

set aside the laws of nature, that not only would make a mockery of science, but

would also mean "the destruction of any meaningful idea of God."(33)

Tillich insists that theologians must join with scientists in rejecting

any notion that makes God into an independent cause of natural events, a natural

object beside others or a being alongside other beings. "No criticism of

this distorted idea of God can be sharp enough!"(34)

Then in characteristic fashion Tillich picks up Einstein's own terminology

and tries to expose its deeper meaning. Einstein had spoken of "the grandeur

of reason incarnate in existence, which, in its profoundest depths, is inaccessible

to man."(35) This reference to a reality,

provoking in humanity a sense of the holy while remaining beyond human understanding,

Tillich identifies as "the first and basic element of any developed idea

of God from the earliest Greek philosophers to present-day theology."(36)

Tillich continues:

The manifestation of this ground and abyss of being and

meaning creates what modern theology calls "the experience of the numinous."...

The same experience can occur, and occurs for the large majority of men, in connection

with the impression some persons, historical or natural events, objects, words,

pictures, tunes, dreams, etc. make on the human soul, creating the feeling of

the holy.... In such experiences religion lives and tries to maintain the presence

of, and community with, this divine depth of our existence. But since it is "inaccessible"

to any objectifying concept it must be expressed in symbols. One of these symbols

is Personal God.(37)

| Repeating

his earlier point, Tillich then admits that the symbolic character of the word

God is not always realized and that the symbol is confused with some supernatural

being which exists out there in an imaginary world of pure spirit. Thus, insists

Tillich, the adjective "personal" can be applied to God only in a symbolic

sense, as it is both affirmed and negated at the same time. "Without an element

of 'atheism' no 'theism' can be maintained."(38)

In what may be the shortest and most concise statement of his own theology,

Tillich condudes his answer to Einstein:

But why must the symbol of the personal be used at all?

The answer can be given through a term used by Einstein himself: the supra-personal.

The depth of being cannot be symbolized by objects taken from a realm which is

lower than the personal, from the realm of things or sub-personal living beings.

The supra-personal is not an "It," or more exactly, it is a "He"

as much as it is an "It," and it is above both of them. But if the "He"

element is left out, the "It" element transforms the alleged supra-personal

into a sub-personal, as usually happens in monism and pantheism. And such a neutral

sub-personal cannot grasp the center of our personality; it can satisfy our aesthetic

feeling or our intellectual needs, but it cannot convert our will, it cannot overcome

our loneliness, anxiety, and despair. For as the philosopher Shelling says: "Only

a person can heal a person." This is the reason that the symbol of the Personal

God is indispensable for living religion.(39)

| In the course of this argument Tillich

refers to a physicist and a philosopher, even as he relates his argument to the

experience provoked by pictures, tunes, or dreams. He affirms the multidimensional

unity of life as an abstraction, and he ransacks the great diversity of life for

the materials with which to build his theological system. Did Tillich find

evidence of divinity in so many places because he believed every dimension of

reality intersected at some point with every other dimension, or did he arrive

at his image of interpenetrating dimensions because he first experienced God in

so many different arenas? It is impossible to say. Yet it is possible at this

point to deny Hannah's criticism that Tillich transformed real life into the gold

of abstraction in such a way that life was lost. Tillich's abstractions flowed

out of his life experience and in turn fed back into life.

|

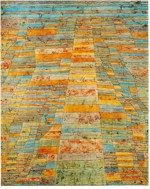

Paul Klee

Highways

and Byways | If there is a biblical

character who typifies Paul Tillich, the strongest candidate is Abraham. For Abraham

followed the call of a God he did not fully know toward a future he did not fully

understand. Like Abraham, Tillich was uprooted from his native country and remained

a pilgrim of the spirit throughout his life. Tillich was also uprooted from the

conventions and even the faith of his own family. He also spent his days wandering

from one place to another, exploring one experience after another, pursuing one

relationship after another. He spoke of the multidimensional unity of life and

in so doing he was able to demonstrate the relationship of science to religion,

helping to heal the "schizophrenic split in our consciousness." This

is not to say that every possibility Tillich pursued turned out to be productive.

He experimented with the use of drugs but quickly concluded that drugs did not

promote a deeper understanding of life's mysteries. He briefly became involved

in politics in both Europe and America but did not find that partisan politics

was his real vocation. Morally, intellectually, and spiritually he tried all things

in order to enter into a deeper relationship with the Creator of all. He spared

no effort in making God comprehensible in terms appropriate to an age of science.

In fact, he turned the tools of science into instruments of theology. While he

rejected the classical arguments for the existence of God, he demonstrated how

the major questions raised by contemporary culture could lead one toward a fuller

and deeper appreciation of the Christian faith. Tillich never claimed that he

had discovered new proof for the existence of God, but he put forward such a persuasive

case for Christianity that it surpasses all the old proofs put together.

Back to the top of this chapter

To

the Index page of God and Science

To GodWeb

Home 1. Hannah Tillich, From Time to Time

(New York: Stein and Day, 1973), p.241. 2. Ibid.,

p.242. 3. Wilhelm and Marion Pauck, Paul Tillich:

His Life and Thought. Volume 1: Life (New York: Harper and Row,

1976), p.1. 4. Ibid., p.5. 5.

Ibid., p.8. 6. Paul Tillich, On the Boundary:

An Autobiographical Sketch (New York: Scribner's, 1966), p.18. 7.

Ibid., p. 16. 8. Hannah Tillich, From Time to

Time, p.242. 9. Pauck, Paul Tillich, p.37.

10. Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology, volume

1 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1951), p.7. 11. Pauck,

Paul Tillich, pp.40-41. 12. Ibid., p. 51. 13.

Ibid., p.92. 14. Paul Tillich, Theology of

Culture (New York: Oxford University, 1959), p.3. 15.

Ibid., pp. 4-5. 16. Systematic Theology,

volume 1, p.18. 17. Ibid., pp. 18-19. 18.

Paul Tillich, The Religious Situation (New York: Meridian, 1956),

p. 62. 19. Systematic Theology, volume 1,

p.212. 20. Paul Tillich, Biblical Religion and

the Search for Ultimate Realty (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1955), p.13.

21. On the Boundary, p.88.

22. Paul Tillich, The Socialist Decision (New

York: Harper and Row, 1977), p.81. 23. Ibid., p. xiii.

24. The Religions Situation, p.10 25.

Ibid., p.107. 26. Systematic Theology,

volume 1, p.206. 27. Ibid., p.205. 28.

Ibid., p. 205, emphasis mine. 29. Ibid., p.15.

30. Theology of Culture, p.42. 31.

Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology, volume 3 (Chicago: University

of Chicago, 1963), pp. 15-30. 32. Ibid., p.

15. 33. Theology of Culture, p.130. 34.

Ibid., p.130. 35. Ibid., p.130. 36.

Ibid., p.130. 37. Ibid., pp. 130-31.

38. Ibid., p.131. 39.

Ibid., pp. 131-32. Return to Index

page of God and Science |

The

theologian dies. His wife returns home and walks upstairs to his desk. Hannah

Tillich describes what she discovered:

The

theologian dies. His wife returns home and walks upstairs to his desk. Hannah

Tillich describes what she discovered: